Loop Hero is what happens when you take multiple current and popular genres in the video game space and cut out every ounce of fat until you’re left with the beating, naked heart at the centre of each one, grotesquely stitched together until it can be its own little thing, rolling around and pulsating to do so.

That’s not a negative thing, because Loop Hero sits on the same coin, but a million miles away from last year’s Hades. It’s a game that respects the player’s time, even if the player doesn’t feel like they’re making much progress. While Hades focused on story beats to aid in masking the progression, Loop Hero offers a riddle of the various game focused elements, leaving the story to only dot the Is.

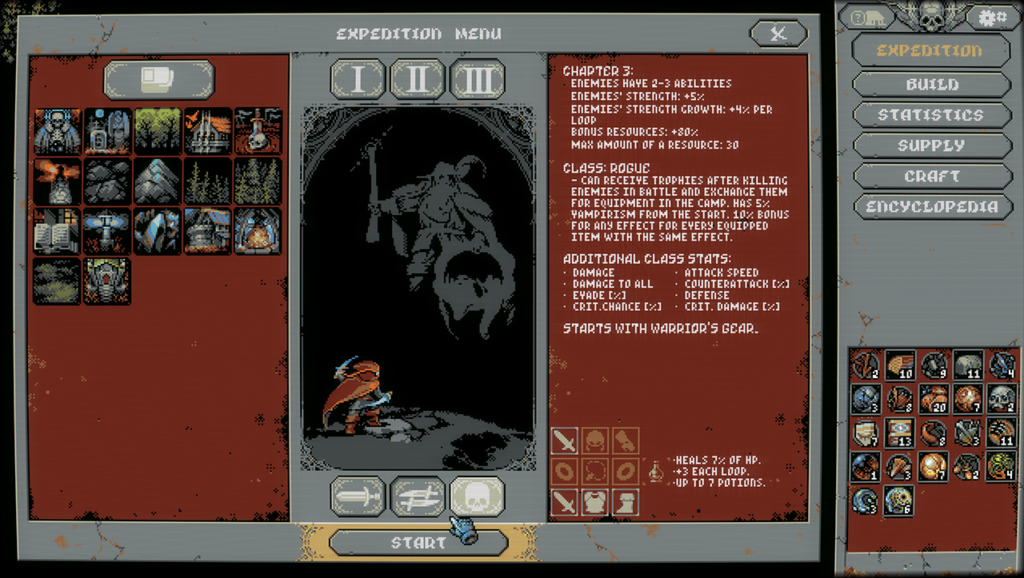

The world has been destroyed. A lich has thrust it into oblivion and there is nothing. You barely remember things, but you know you must travel in an attempt to defeat this villain that has cast the world into the void. Upon the first successful completion of a loop, you’re thrust into a makeshift camp by other survivors of the apocalypse and can begin using the things you’ve collected from the enemies in the loop to build up the camp to a more hospitable and survivable thing.

No one element of Loop Hero is deep. It has base building, but it’s mostly very light on strategy, instead of more of a tech tree that eats resources.

Its loot mechanic while on an expedition is fairly rudimentary, with very few stats to manage.

You have zero control over the combat and while exploring the loop, it’s done automatically like an idle game.

There’s deck building, but again, you’re not trying to build ‘the perfect deck’.

So why am I enamoured with this game?

Because by reducing every element to a simplistic version of itself, it can begin to hide different elements within it to unravel to the player through their own intuition or even by relying on a wiki. It took ten hours before I noticed that there was a stamina system in combat or that the Oblivion cards – which destroy a resource you’ve placed – can be used to ‘cheat’ the system and grind out the resources from a completed mountain range or to reduce the number of enemies a particular tile can produce.

In 2010, Edmund McMillen highlighted that Super Meat Boy is built upon the philosophy of ‘risk and reward’, popularising it in the public consciousness as a trait found in every video game. Loop Hero is 75% that.

The deck-building mechanic comes into play differently to other ‘deck building games’. You earn the cards you’ve chosen to go into the loop with by doing stuff in the loop. Defeating a monster, completing resources etc. However, these cards don’t always help you. Mountains and meadows can aid you in giving you more life and attack, but a full range of mountains will begin to spawn harpies and gargoyles will show if you surround a treasury with the required eight tiles.

You’ll earn better loot from different enemies, but that requires you to begin placing things down onto the loop itself. Do you risk the ruins on a cluttered loop, knowing that the worms inside can participate in any battle adjacent to them? Do you begin building villages for quests, which are, again, just as simple as everything else (you run into the monster with ‘quest’ on it, kill it and get the reward on the next pass) and place wheat fields next to them, only to be inundated with scarecrows and bandits in the future?

Old Adage

Everything in the game is ‘risk and reward’, a constant shoving and tugging to maintain balance in a dead world that you’re slowly attempting to bring back to life.

Now, yes, the game does feature a small grind to level up facilities, which will help you on the loop and such, but it does the beautiful thing of being delightfully quick between each round. With its incredibly quick method of immediately getting you back into the game, it never makes taking the risks that these games constantly present a hassle. Sometimes you have to see if you can beat the boss, because what if you do?

You can pull yourself out of the loop at any time, losing 60% of the resources or on death, 30%. Death doesn’t just mean the end and while it’s a meagre amount, you’re only a couple of clicks away from doing it all over again.

If you pass the campfire – kind of like Monopoly – you’ll be able to leave with everything and save yourself if need be. But… what if you could make one more loop? Like, surely you can make it?

No. You never do. BUT SOMETIMES YOU DO. I can quit whenever I want. Bet it all on black.

I also really love the look of this game. It’s a grungy, dirty little video game aesthetic that you don’t get out of pixel art anymore. Everything has to be beautiful and sleek, no one ever considers the ugliness of the era of PC games that it draws upon.

With it reducing everything down, when you actually sit down to play the game, it is absolutely in the vein as some other dungeon crawlers, except on the surface it seems like loot is as interchangeable and loose as any other randomly generated rouge-lite. Except because Loop Hero doesn’t show all its cards on the table immediately, the smaller focus can mean a whole lot of different things for how the run plays out.

I went full hog into Vampirism, so I was getting tonnes of health back from enemies but neglected any of the other few stats that you have to manage. So while I was sucking the life out of people, my poor necromancer had very little defence and died a gruesome death to a barrage of ratwolves.

But it doesn’t want you to cling to loot, it just wants you to ensure that you’re absolutely laser-focused on managing the very tiny numbers so that you can survive. Risk, reward. Don’t get attached to the level three-ring because it’s colour-coded orange, the game’s version of ‘legendary’ loot because this level six-blue (magic) ring provides more of what this has, just give up on the other two statistics.

Or do you? More attack speed is sweet, but also, the added defence and magic damage is useful too…

Loop Hero is great. Its distilled, simplistic hooks drag you into its ever-unfolding nature in the vague hope that you do finish it. It’s not a game that shows its hand as soon as it can, instead opting to lead the player by a small stick with some fudge on the end, because fudge is better than a carrot. It proves that massive fancy flourishes aren’t needed to make a good game and that over-complication is a trick these indie games fall into far too often.