There is an odd vibe in the air whenever I think about Travis Strikes Again, Grasshopper’s return to No More Heroes and Suda’s return in a long time to the actual director’s chair. A game that in one part is as daft as the previous two entries, partially entirely different and then also, deeply profound in a way that comes from the leftfield.

For a game that appears to pride itself on its parodies and continuation of the story of a man who jiggles his sword like a 14-year-old boy watching his first porno, Travis Strikes Again is something that left me feeling this upbeat melancholy. Bitter sweetness washed over me with glee, as Travis monologues to an empty room about his inner-most thoughts, while just under an hour ago, a homage to classic genres opened up to me.

Goichi Suda reduced the team size down to just a handful of people for this project, proudly building it in the Unreal 4 Engine and returns to Grasshopper’s rather humble beginnings. After seeing the rise in indie games a mainstay of the industry, Suda wanted to recreate the feeling they had back when they first started and it shows here, not only as a piece of media that looks back on Grasshopper’s past but also its contemporaries. It’s fascinating.

TSA sees Travis seven years removed from No More Heroes 2, older and wiser, but still invested in his hobbies – to a fault. He’s effectively run away from something and is hiding out in the woods of Texas, in a splashy trailer. While he hides, a guy by the name of Badman, the father of NMH1’s second rank boss, Bad Girl, hunts down Travis to exact revenge for killing his daughter. In the process, they’re sucked into the Death Drive Mk2, an elusive video game console with supernatural abilities – like resurrecting the dead. Now, Travis and Badman must hunt for the ‘Death Balls’, complete each game contained within and discover the mysteries the console brings with it.

The story – is typical Suda fashion – is utterly bananas, which is like this lovely security blanket as you are pelted often with introspection, depression and positive messages.

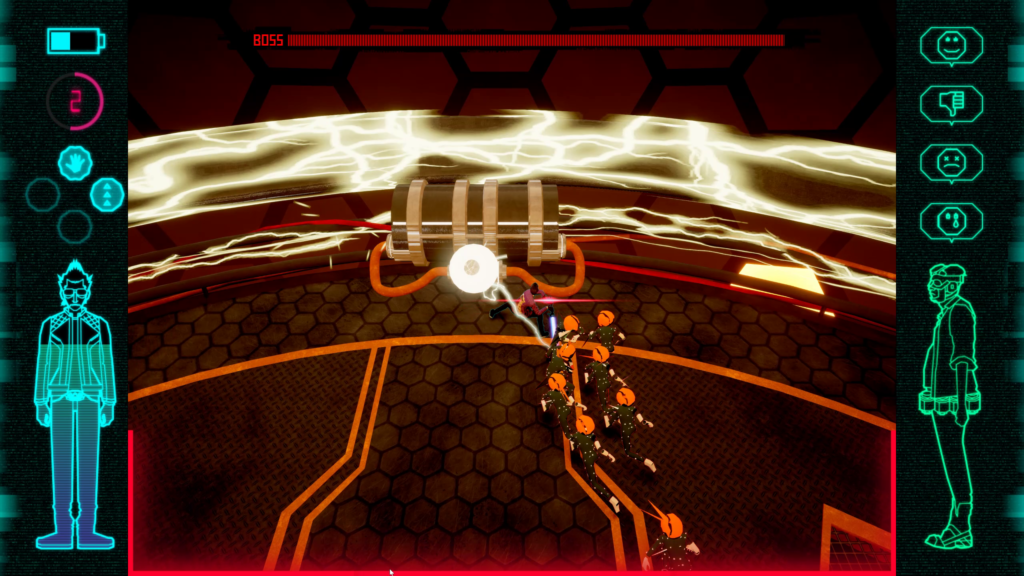

No More Heroes’ mechanics have been reduced to that of a top-down view (that will occasionally pan around or become a side-scroller) and uses a more traditional light and heavy swing, rather than the low/high mechanics seen in the first two games. It translates well, but the mileage in how well it goes per game varies. I thoroughly enjoyed my time in the first couple areas, but it became more of enjoying the ‘vibe’ than the actual game itself after awhile.

There’s an awesome looking vector graphic drag race game that is so maddening that I genuinely have a blind spot in my mind of beating it. Areas in the Coffee and Doughnuts to do with combat became tedious quick, while the game immediately piqued my interest once it began doing No More Heroes’ – and Grasshopper’s – best work with breaking the fourth wall with the final few areas.

Swings and roundabouts, I guess, are just part and parcel for a variety pack of games that ultimately seem to be a gateway to where Suda’s true intentions appeared to be and that’s telling more story with Travis that wouldn’t particularly fit anywhere else.

TSA might follow the first game’s heavy and unsubtle approach to the analysis of culture and the self, but it does it with a thundery undertone of being older, wiser and at a juncture in life. Goichi Suda has said that Travis does pull from himself as inspiration – presumably why Travis felt like the only constant between NMH1 and 2 – but this feels like seeing an old friend after so many years apart.

Sure, Suda has actively been involved with a majority of Grasshopper Manufacture’s games, but he hasn’t actively directed anything in a long time. There’s been no true ‘Suda Joint’ as the Shadows of the Damned marketing team would say.

This not only feels like the perfect addendum to No More Heroes but also for Suda to truly let loose. It not only makes logical sense within the context of the lore of the game but also in the context of how the game presents itself.

It’s a Commemorative Game. A celebration, reflection and ultimately, a platform to be used. I don’t think in the entire time I’ve played video games, I’ve seen such heartfelt love for games within a game. Easter eggs come, Easter eggs go. References here and there. Sometimes you see stuff in other games where it’s a cross-promotional thing, like when Team Fortress 2 was the hot commodity to get advertising into. This is different.

Travis can access a PC to purchase unlockable shirts that all straight-up feature key art from indie developers, with names attached and other than what I can imagine being “send us a PSD with the art in”, this feels like a celebration of what games are now, rather than a cheap marketing trick.

It’s a glimmer of pure positivity in an industry so fraught with fragility, that the game itself begins to explore.

Coffee and Doughnuts take what might have been this grandiose mech game set in vast areas – akin to Armoured Core – and utilise an adventure game space – weirdly enough similar to another From Software series, Echo Nights – to explore why a character trapped in an endless cycle of nothing to do would want to kill themselves in elaborate mystery. The genre Brian Buster Jr. came from moved on from the old days, leaving this to forever loop with nothing new to do.

The maddening Golden Dragon GP features a particular favourite area of mine, as Travis finds himself in a classic style single room from Japan, in awe at its splendour. However, look closer. It’s dingy. Lonely. Barely any furniture, a simple room for simple, cheap living. A VR headset sits on the table for escaping. All the action takes place outside of the room. A beautiful, yet sad song plays over the top.

When translated the songs lyrics talk of leftovers for breakfast, how tears overflowed. This room… it’s probably where a lot of people started – in particular here, developers – while making their masterpiece. It might be where Suda started. Look back upon the past and remember where you came from. It’s not too dissimilar to Travis’ motel room.

Travis Strikes Again goes even as far to explore development hell via foreshadowing in its text adventure/visual novel sequences, Travis Strikes Back. A character prominently featured in the trailer for No More Heroes 3 talks about how the lead developer got irate with the team and canned the whole project, even though they worked hard on it.

(The game does go into the fact this now CEO brutally beat her and Travis literally Strikes Back because of this)

You then play through a small, Unreal 4 test area that is a gateway into yet another game as an appreciation for where video games even spawned from, as it takes on an Asteroid approach, with thick neon, vector lines that you can imagine inside a rectangle cabinet, searing into your very eyeballs. From the modern extreme to the next. TSA wants you to appreciate where your games come from.

It does this best in the very large surprise return of Garcia Hotspur and Johnson from Shadows of the Damned. This was a game that Suda expert, Ghenry Perez, described as having a more interesting history than game. What started as a unique and at the time revolution for the horror genre, wound up being a shadow of its former self.

Kurayami was to be more focused on fear, especially of what lays in the dark. The townsfolk would change, as well as the player character. It was a concept, as one of the recurring characters in the game explains, too big for some publishers to grasp. The technology hadn’t caught up and no one would dare take it on. It died so that Garcia Hotspur’s adventure could live.

But even though Shadows of the Damned failed to be the hit it was poised to be by EA’s brief marketing campaign that slotted Suda and his old colleague, Shinji Makami – Resident Evil 4, Evil Within – as leading the project when in reality, they were simply in overlooking roles. Executive Director. He pitched something and something else got made in its stead.

While a black sheep mark on Suda’s legacy, he appears to hold it dear despite everything that happened through the development. Travis Strikes Again teases a sequel by straight-up setting up the plot for a game that’s supposed to be setting up the plot for another game. It is a purely fascinating thing to see play out and I adore it.

This love of projects that didn’t happen as planned occurs again in a sequence during Strikes Back. Travis is challenged by four mysterious characters, all from games that Grasshopper never managed to make. He chops them down without remorse, as Suda and his team probably had to in the past to make room for the hells of profitable development.

There’s even a reference to Juliet from Lollipop Chainsaw, where they begin to explore what happens to these characters after their games hit big and suddenly, sidelined, never to be seen again.

All of this is intertwined via Travis, who’s conversations with the bosses of each area delve deep into the psyche of the character, but because the crack of the fourth wall has been split wide open, it indirectly talks to the player. Games are for playing, not living. There’s no life without sorrow.

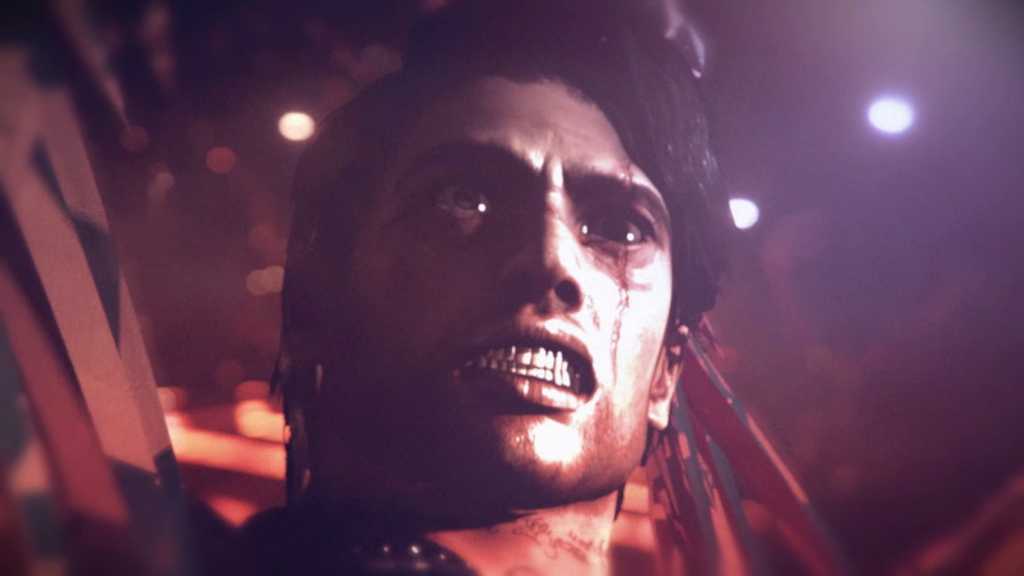

Giving up isn’t an option. His lonely, silent monologues – that sit in stark contrast to the loud, constantly noisy game – explore a side of the character rarely seen. In previous games he’s quick to get over the death of Thunder Ryu, his master and Bishop’s death takes a backseat to the plot of No More Heroes 2, even though it’s what kicks it off.

Here, 7 years on from everything, it feels as if things are starting to take their toll on Travis. You can’t shrug everything off. Sometimes you have to look inwards, be frank with yourself and how you plan to face the future after these events.

While the whole game might ooze a goofy, humourous vibe, it is simply masking the truth. You can’t be this all your life. You’re older now, enjoy what you enjoy, but there’s more to life out there. If you’re a newer, younger player buying this on Switch, in a Steam sale or on PS4, maybe coming off the recent rereleases of NMH1 and 2, don’t make your life about a singular aspect.

Suda and Grasshopper have survived by developing and producing games through their career by taking chances, not following the easy road and each game, while some similar in spots or straight-up sequels, have done something vastly different than before.

Even duds like Diabolical Pitch, a Kinect game about demon baseball or the low-key Sine Mora, which featured a depressing wartime tale through the eyes of a side-scrolling shooter. Even Lollipop Chainsaw, which is Grasshopper’s biggest financial success, once again goes against the grain by using the cheerleader and high school aesthetic in a genre dominated by heavy rock, metal, angels, demons and men.

You cannot rely on being the same, stagnant thing through your entire life.

Travis is the entwining factor, as Travis is the embodiment of this lesson. While No More Heroes 2 didn’t utilise much – if any – of Suda’s exploratory ideas, it did situate Travis back in the No More Heroes Motel, his dingy place from the first game. A man filled with riches from his previous exploits and in possession of his first real fight’s mansion, has decided to remain where he’s most comfortable.

In TSA, his trailer is a stretched-out version of the motel. Even when returning to Sylvia and his family, they’re in possession of a mansion and his daughter an unwavering success online.

He wants to comfort and familiarity, in a world that you can’t just settle for that anymore. You have to be more than the familiar. I think it’s partially why Suda and Grasshopper feature so many different titles in their unlockable shirts. These games tried something vastly different in an industry that is filled to the gills with familiarity.

He even shows sympathy with Dr Juvenile, one of the main antagonists of the game after discovering what has happened to her in the past – without the caveat of doing this after beating or killing them.

The world might have No More Heroes, but it doesn’t mean we have to let life escape us. Don’t get bogged down with just one thing. Face it head-on. Piledrive it into submission. Win.

Travis Strikes Again ends with Travis seeing that he has to face things head-on, his bloodlust raring to go once again and that he can’t hide from his problems any longer. The game eventually fades back into an Unreal test area.

You’re told they’re in development.

It looks like Suda and Grasshopper Manufacture are finally taking this on themselves, facing the third entry and then they too, can move on.